Home » Solaires generates clean electricity — from ink

Solaires generates clean electricity — from ink

Canadian startup’s breakthrough opens the door to solar panels that are ultra-thin and translucent.

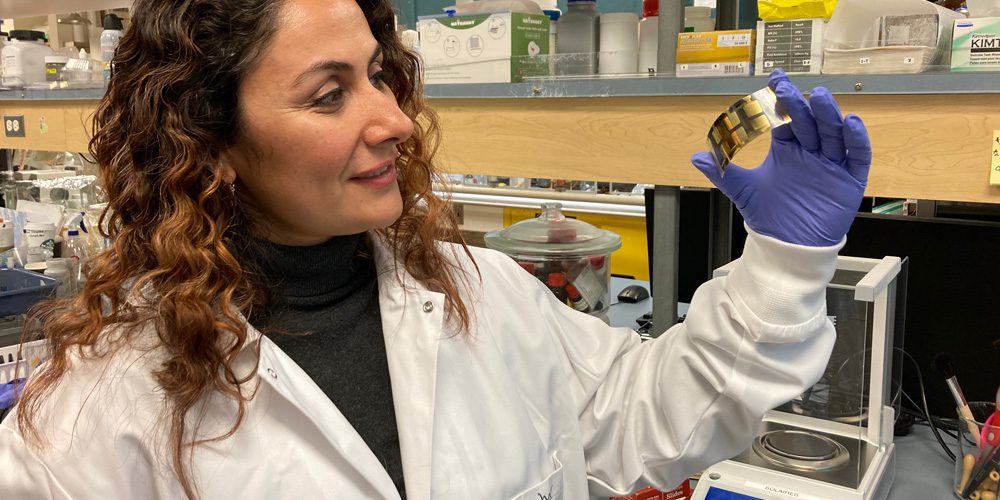

Standing in her lab at the University of Victoria, Sahar Sam holds a solar cell about the size of a business card between her thumb and index finger, slowly bends it into the shape of a rainbow and smiles.

In her hand, she holds the future of solar panels.

According to Sam, the next generation of solar panels — thin, light, flexible and sometimes even translucent — will be applied to a multitude of surfaces, from smartwatches and cellphones to windows and electric vehicles.

“We want to be able to turn any surface into something that generates electricity, not just the roof,” says Sam, whose startup, Solaires, is at the forefront of making this happen. The more expanses we can cover in solar panels, the faster we can transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy.

“To keep the 1.5-degree limit within reach, we need to cut global emissions by 45 percent this decade,” United Nations secretary-general António Guterres said in April. “First and foremost, we must triple the speed of the shift to renewable energy.”

As we make that shift, however, the infrastructure for clean energy also needs to get greener. Although generating electricity from solar energy doesn’t produce any carbon emissions, manufacturing conventional panels has a significant carbon footprint. In fact, a 2020 study published in Joule found that within the next decade, annual carbon dioxide emissions from the global solar industry will exceed those of international aviation today.

The next generation of solar panels can reverse that trend, says Sam. They will be greener and cheaper to produce and may even generate more electricity than existing arrays. And they may one day even mitigate those aviation emissions by being affixed to lightweight, electric airplanes.

Disrupting the solar industry

Sam, who is originally from Iran, moved to Victoria more than a decade ago to pursue her PhD in mechanical engineering. While Iran is rich in natural gas and oil, it is also bathed in sunshine, and Sam had long been interested in materials that can absorb the light and generate electricity. “We have sun for free,” she says. “We need to use it.”

During her doctorate, she developed and patented a technology for making transparent conductive layers, which are components of solar panels. A few years later, in February 2020, she teamed up with Fabian de la Fuente, a former colleague who had experience running startups. Together they launched Solaires. The company has quickly grown to more than 20 employees and secured several patents around its materials and manufacturing process.

“What we do has to serve humanity,” Sam says. “This is my turn to give back to society, give back to Mother Earth and help the next generation be able to live here and enjoy the planet.”

To understand why the solar industry is ripe for disruption, one must first understand how solar panels are made.

Solar panels are composed of several layers. In traditional panels, the semiconductor layer is made from silicon, which comes from quartz rocks that need to be mined and extensively refined. “It’s a dirty process for making something that is supposed to be green,” Sam says.

Because silicon is processed at temperatures exceeding 1,000 degrees Celsius, it must be sandwiched between layers of a material such as glass that can tolerate extreme heat, meaning the final solar panels are heavy and rigid.

Solaires is trying to replace it with another crystalline material called perovskite, which is also a semiconductor. In their lab, Sam and her colleagues combine chemicals to make a unique perovskite-containing solution called Solar Ink.

The raw materials used to make Solar Ink are abundant and don’t require extraction or purification. And perovskite doesn’t have to be processed at high temperatures, so it can be sandwiched between plastic, making the final product thin and flexible. A perovskite layer is at least 1,000 times thinner than a silicon layer, according to Sam.

“It’s an easier, greener and lower-cost process of making solar panels,” she says, adding that Solaires is striving to develop a perovskite solar cell manufacturing process that emits 40 percent less greenhouse gases and operates at a lower capital cost than that of existing silicon solar cells.

Independent research suggests such a goal is well within reach.

A 2020 study published in Science Advances found that solar cells that exclusively use perovskite produced less than half the greenhouse gases per unit of energy compared with solar cells that use perovskite and silicon. Meanwhile, the cost per watt for silicon solar technology is reportedly almost 50 percent higher than that of perovskite and another study found that perovskite solar cells could be twice as efficient as silicon ones.

A bonus is that perovskite can be modified to absorb different wavelengths of light, while silicon always absorbs the same part of the spectrum. In other words, perovskite solar panels could function under indoor lights while silicon solar panels only work in the sun.

“If we had it on our laptops right now, they could be charging,” says Sam.

There are, however, drawbacks to perovskite cells. The biggest is their lifespan. Today, solar panels come with 20- to 25-year warranties. But perovskite solar cells currently only last about three to five years.

“Perovskite is very sensitive to humidity, oxygen and even light. So over time, the amount of power it can generate decreases,” Sam says, adding that a decade ago, when the material was first trialled, it only lasted a couple of hours. “The technology and lifetime are going to improve, but we’re starting with what we have.”

For Solaires, that means entering the market through goods that typically last less than five years, like cellphones, smartwatches and tablets. As the technology advances, the company plans to move on to products with longer lifespans, such as electric vehicles.

The race to develop perovskite solar panels

More than a dozen companies around the world are racing to develop perovskite technologies, but Solaires is leading the pack. In December 2021, Solaires became the first to manufacture perovskite ink at industrial scale, and the company is now selling its Solar Ink to solar panel makers. It is also in talks with manufacturers of internet-connected devices and electric vehicles who are interested in adding perovskite solar panels to their products.

Back at the lab, Sam and her colleagues are working on fine-tuning their ink and fabrication process, with the aim of making larger solar cells with cheaper materials and testing the final products. In the future, Solaires plans to license its technology to manufacturers.

Investors and governments are also betting on perovskite solar panels. The company has received more than $7 million from equity funding and federal and provincial grants, the majority of which are from the National Research Council of Canada’s Industrial Research Assistance Program.

Precedence Research estimated the global solar power market at U.S.$197.2 billion in 2021 and predicted it would grow by 7.2 per cent a year to U.S. $368.6 billion by 2030.

But for Sahar, it’s not about winning a race or striking it rich.

“My personal belief, which I learned from my parents, is to be good, do good and that’s the only way that you feel good,” Sam says. “People say that your company is your baby. Solaires is truly my baby because I’m growing something that I truly believe in.”

Solaires is supported by the RBC Women in Cleantech Accelerator. Discover other women-led ventures that are helping to solve the world’s climate challenges.

Photo credit: Raina Delisle

MaRS Discovery District

https://www.marsdd.com/

MaRS is the world's largest urban innovation hub in Toronto that supports startups in the health, cleantech, fintech, and enterprise sectors. When MaRS opened in 2005 this concept of urban innovation was an untested theory. Today, it’s reshaping cities around the world. MaRS has been at the forefront of a wave of change that extends from Melbourne to Amsterdam and runs through San Francisco, London, Medellín, Los Angeles, Paris and New York. These global cities are now striving to create what we have in Toronto: a dense innovation district that co-locates universities, startups, corporates and investors. In this increasingly competitive landscape, scale matters more than ever – the best talent is attracted to the brightest innovation hotspots.